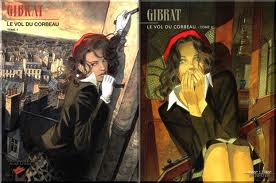

One day, if I write a spy story set in Nazi-occupied Paris, with a bright young heroine named… Maybe her name doesn’t matter, but I would definitely write a scene where she escapes over the rooftops exactly as Jean-Pierre Gibrat’s heroine, Jeanne Cadrieux, does in Gibrat’s two-volume bande dessinée titled Le Vol du Corbeau (The Flight of the Raven).

Jeanne is shown (extreme left) on the cover of volume 1 of Le Vol du Corbeau, clinging perilously to the side of a building, high above Paris. Those white gloves will get awfully dirty, Jeanne!

Jeanne is shown (extreme left) on the cover of volume 1 of Le Vol du Corbeau, clinging perilously to the side of a building, high above Paris. Those white gloves will get awfully dirty, Jeanne!

She is shown on the cover of volume 2, no gloves but still with the red beret. She is aghast at what she has done. And she has good reason. She has just shot a German soldier with his own rifle.

Le Vol du Corbeau is the sequel to Gibrat’s earlier bande dessinée Le Sursis which starred Jeanne’s sister, Cécile. [See my post of 29 July 2012, tagged under Gibrat].

Gibrat is the unquestioned master of setting. Volume 1 of Le Vol du Corbeau mostly takes place on the rooftops, among the chimney breasts of Paris’s ubiquitous mansard roofs. Volume 2 is set largely on the river, aboard one of the Parisian barges that sail up and down the Seine.

The story in a nutshell:

Volume 1 of Le Vol du Corbeau begins with Jeanne in jail. She has been reported for black market (marché noir) activities and the police have searched her apartment and discovered a cache of weapons. Jeanne is working for the French Resistance.

While the local police chief ponders whether or not to hand her over to the Gestapo, a burglar named François Michaud is tossed into Jeanne’s cell. François helps her to escape, and the two of them flee over the rooftops.

François then takes her to his friends who own a barge, and they sail from Paris.

Complication of Volume 2: A German soldier is stationed aboard the barge. Further complication: Jeanne shoots him when he tries to force himself upon her. What to do with the body?

It’s never good to tell an ending. Please read the book. It’s well worth it. [Only available in French, I believe]. Those who would like to see Jeanne and Cécile reunited will not be disappointed. Likewise, those who would like to see Jeanne and François become lovers.

![US Wickes-class destroyers about to be transferred to the Royal Navy [Public domain]](https://secondbysecondworldwar.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Wdestroyersbases1-234x300.jpg)

![US base Kindley Field, Bermuda [Public domain]](https://secondbysecondworldwar.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Wkindleyfield-150x99.jpg)

![London 'tube' (metro) station in use as air raid shelter [Public domain]](https://secondbysecondworldwar.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Wblitz1-240x300.jpg)

![Anderson shelter shown above ground [photo taken by Simon Speed, now Public domain]](https://secondbysecondworldwar.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/Wblitz2-150x112.jpg)

![London children in aftermath of air raid, September 1940 [Public domain]](https://secondbysecondworldwar.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/Wblitz1940-300x235.jpg)

![Leon Trotsky (centre) with friends in Mexico, 1940 [Public domain]](https://secondbysecondworldwar.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Wtrotsky1.jpg)

![Trotsky's grave in Mexico City, Attribution: Share Alike 3.0 Unported [GNU Free Documentation]](https://secondbysecondworldwar.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Wtrotsky2-225x300.jpg)

![Camel Corps Memorial, London, LondonRemembers.com, [Creative Commons]](https://secondbysecondworldwar.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Wcamelcorps.jpg)

![Curiosity, Martian lander, NASA [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://secondbysecondworldwar.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Wcuriosity-300x200.jpg)

![Invasion 1940---by Peter Fleming (1957) [Photo by Edith-Mary Smith]](https://secondbysecondworldwar.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/Winvasionbk-e1348697920609-198x300.jpg)