On the morning of 10 May 1940, American journalist Claire Boothe Luce was asleep in her room on the top floor of the US embassy in Brussels when a maid shook her by the shoulder, urging her to wake up because the Germans were coming. Hitler’s invasion of Belgium, the Netherlands and France was underway.

On the morning of 10 May 1940, American journalist Claire Boothe Luce was asleep in her room on the top floor of the US embassy in Brussels when a maid shook her by the shoulder, urging her to wake up because the Germans were coming. Hitler’s invasion of Belgium, the Netherlands and France was underway.

From her window, Luce could see twenty or so planes flying in formation, high above the city. In her book Europe in the Spring (Alfred A. Knopf, NY, 1941), she describes hearing the whistles of falling bombs, and the explosions that followed. Following the all-clear, she ate breakfast at a sidewalk cafe on Place Rogier. The Germans had already passed through the Duchy of Luxembourg ‘like a cheese-knife,’ she was told, but French cavalry had arrived in Brussels to help the Belgians. She was also informed that British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, was struggling to defend himself in the House of Commons. He was blamed for the fiasco in Norway, where the British expeditionary force had suffered a series of reverses leading to its eventual withdrawal.

Across the Atlantic, US President, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, held a meeting in the Cabinet Room of the White House. It was 10.30am (Washington time), and his principal advisors and military chiefs were there to discuss the developing crisis in Europe. Secretary of Commerce, Harry Hopkins, was presenting a worrisome account of the shortage of strategic raw materials when news arrived from London that Chamberlain had resigned as Prime Minister and been replaced by Winston Churchill. Roosevelt told his Cabinet that Churchill was the best man that England had.

Across the Atlantic, US President, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, held a meeting in the Cabinet Room of the White House. It was 10.30am (Washington time), and his principal advisors and military chiefs were there to discuss the developing crisis in Europe. Secretary of Commerce, Harry Hopkins, was presenting a worrisome account of the shortage of strategic raw materials when news arrived from London that Chamberlain had resigned as Prime Minister and been replaced by Winston Churchill. Roosevelt told his Cabinet that Churchill was the best man that England had.

“In modern times,” Roosevelt warned Americans later that evening, in a speech at Constitution Hall, “it is a shorter distance from Europe to San Francisco, California, than it was for the ships and legions of Julius Caesar to move from Rome to Spain or Rome to Britain.”

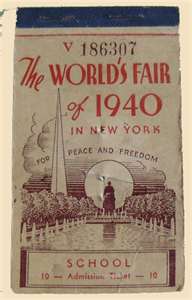

The following day, 11 May 1940, the New York World’s Fair—which had been closed over the winter—reopened with great ceremony. Technology and progress were an overriding theme and crowds flocked to view the wonders that the future held in store. In the Westinghouse pavillion, they could witness the sterilizing effect of flashes of light on water droplets—a demonstration that was named, ironically, the Microblitzkrieg.

The following day, 11 May 1940, the New York World’s Fair—which had been closed over the winter—reopened with great ceremony. Technology and progress were an overriding theme and crowds flocked to view the wonders that the future held in store. In the Westinghouse pavillion, they could witness the sterilizing effect of flashes of light on water droplets—a demonstration that was named, ironically, the Microblitzkrieg.