Barbecues, fireworks, and beach parties are fine ways of celebrating July 4, but we should also remember the people who have put themselves in harm’s way to make possible the freedoms that Americans enjoy. My favorite way of commemorating America’s independence is to recall World War II and my father’s service in that conflict.

The Second World War occupies a mythic place in the American psyche, and rightly so. Like the American Revolution and Civil War which preceded it, World War II presented a dire military threat to American sovereignty. It was the first and only American war that required both mass mobilization and deployment of American troops throughout the globe.

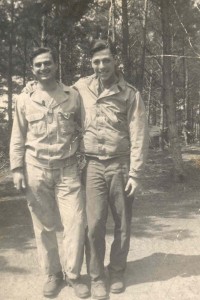

My father wasn’t a particularly distinguished soldier, though he served in many important campaigns, including the Normandy invasion, the Battle of the Bulge, and the Rhineland Campaign. Like most men and women in uniform, he was an ordinary person coping with some extraordinary situations and would never consider himself a hero.

My father wasn’t a particularly distinguished soldier, though he served in many important campaigns, including the Normandy invasion, the Battle of the Bulge, and the Rhineland Campaign. Like most men and women in uniform, he was an ordinary person coping with some extraordinary situations and would never consider himself a hero.

As an Army radio truck operator for the 327th Fighter Control Squadron, part of the Ninth Air Force, my father was usually five-to-ten miles behind front lines. You might say that he lived on the fringes of history, and you’d be right, except during the Battle of the Bulge—Hitler’s startling counterattack in the Ardennes—when my father was right on the front lines in Liege, Belgium, where he worked tough twelve-to-sixteen hour shifts while buzz bombs were pouring into that city at 100-plus per day.

It was the only time in his life that my dad smoked. During the six weeks that the Battle raged—from December 16, 1944 to January 25, 1945—my father puffed as frequently as the bombs flew. As a sergeant, he supervised two men in the radio truck: a PFC and a corporal who would monitor radio broadcasts and perform clerical duties.

Fighter Control soldiers would guide lead fighter pilots in a five-plane fighter squadron to their targets, and, if they were lost or hit, help them return to base. If a pilot was lost or hit, a fighter control technician, usually a sergeant or a corporal, would listen on earphones for a signal emanating from the aircraft of the lead pilot. He would then turn a little wheel inside his truck until the signal reached the “null” or softest volume. That would give him the angle of the lead pilot relative to a controller in an operations block on the ground. Finally, the radio man would transmit that angle to the controller.

Technicians in two other radio trucks in the vicinity would repeat the process, and the controller would plot all three angles on a graph. The point of intersection was the pilot’s location. Once that information was obtained, the controller could talk the pilot back to base.

Determining angles was tricky. The radio man had to listen carefully for the null volume. There was a sound that was almost identical which was 180 degrees off. If he got the wrong angle, the pilot could fly out to sea, where death was almost certain.

In the two years that my father was overseas, the 327th Fighter Control Squadron, some 300 men-strong, never lost a single pilot. It was one of the great unsung achievements of the ordinary enlisted men who operated the fighter control system.

For someone who was deployed overseas, my father enjoyed relative safety. He wasn’t a combat soldier, worked an eight-hour shift most of the time, and, unlike infantrymen and pilots, had frequent contact with civilians. During several months before and after the Bulge, he lived with a Belgian woman with whom he was deeply in love.

But relative safety isn’t total safety. My father almost lost his life several times.

During a softball game with his buddies in a French forest shortly after the Normandy invasion, a sniper’s bullet missed his head by a couple of inches. My father was slow in understanding what had happened to him and never told anyone about the incident.

And a V-2 rocket narrowly missed a Belgian mess hall where my dad and about 100 other soldiers were chowing down. Plates clanged, forks flew, and everyone ducked under the table. My father, one of the first people to pick himself up off the floor, looked around and saw a roomful of ghosts. Every man’s face was drained of color.

The rocket, which landed in some then-unknown area nearby, hadn’t exploded; it was a dud. Or so the radio men thought. Days later, while my father was walking to work, the rocket exploded. He hit the ground, and shrapnel flew over his head. Fortunately for him, he was just outside the flying bomb’s kill radius of about 75 feet. The guys in the bomb squad weren’t as lucky. They died trying to disarm the warhead.

One day my father was working with his corporal when a buzz bomb flew particularly close to the radio van. The growling sound kept getting louder and louder, and grew to a fever pitch. The corporal tried taking a drag from a cigarette to calm his nerves, but he couldn’t do it. His hands were shaking so frightfully that he could not put the match he had lighted in contact with the tobacco. Frustrated, he threw the matchbook and cigarette to the ground. My dad picked them up, lit the cigarette, and returned it to its owner.

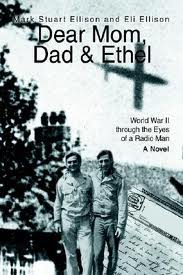

One of my father’s favorite diversions was writing to, and receiving letters from, his parents and sister, Ethel. My father would address his V-mail “Dear Mom, Dad & Ethel”, which became the title of a book he and I co-wrote about his wartime experiences. Dear Mom, Dad & Ethel contains about 100 of my father’s best V-mail letters written from England, France, Belgium, and Germany. Aside from the letters, Dear Mom, Dad & Ethel is a war story and a love story. Extensive historical material is weaved into the text, which includes a bibliography and hundreds of endnotes.

One of my father’s favorite diversions was writing to, and receiving letters from, his parents and sister, Ethel. My father would address his V-mail “Dear Mom, Dad & Ethel”, which became the title of a book he and I co-wrote about his wartime experiences. Dear Mom, Dad & Ethel contains about 100 of my father’s best V-mail letters written from England, France, Belgium, and Germany. Aside from the letters, Dear Mom, Dad & Ethel is a war story and a love story. Extensive historical material is weaved into the text, which includes a bibliography and hundreds of endnotes.

We couldn’t write Dear Mom, Dad & Ethel as non-fiction because after sixty years, my father’s memory wasn’t perfect and we wanted to preserve the anonymity of people whom we negatively portrayed. That said, Dear Mom, Dad & Ethel is about 90 percent true, except for the sex scenes, which are absolutely true, as are the wartime letters.

My father “got around” in wartime Europe. Naive about sex before the war, he received a thorough education in it shortly after arriving in London in 1943. The lessons continued throughout the war.

In wartime Europe, a man in uniform could walk into almost any bar or pub, and after a few minutes of casual conversation, start getting physical with a woman. It wasn’t because she was a slut or a whore; it was because she was often ill-fed, hadn’t seen her husband or boyfriend in months or years, and was afraid of dying in air raids.

In this regard, American soldiers had a great advantage over their British counterparts. Far better paid than the Brits, the Yanks could afford hard liquor. The Brits, as a rule, could only afford cider. My father and his buddies could also buy ladies a good meal.

In this regard, American soldiers had a great advantage over their British counterparts. Far better paid than the Brits, the Yanks could afford hard liquor. The Brits, as a rule, could only afford cider. My father and his buddies could also buy ladies a good meal.

This situation inspired a common refrain of British soldiers which became famous in the run-up to the Normandy invasion. In a survey in which they were asked what their chief complaint about Americans was, many replied “overrated, oversexed, and over here.”

The women my father bedded while he was overseas meant little more than a good time to him, except for a Belgian seamstress whom we call Denise. Denise and my dad had an almost-telepathic connection. They finished each other’s sentences, and each seemed to know what the other was thinking before a sound was made. They ate and slept together whenever their schedules permitted. It was the most natural thing in the world.

Like most Belgians who worked in the textile town of Verviers, Denise had little food. The retreating Germans had confiscated much Belgian produce and property, and the region’s major industries had been decimated by the war. So whenever my father went to visit Denise, he’d take a second helping from the G.I. chow line and transport it to a grateful girlfriend.

You can read more about their romance in Dear Mom, Dad & Ethel: World War II through the Eyes of a Radio Man, available on Amazon.com, Barnes & Noble.com, and iUniverse.com. In addition, please visit my website at www.momdadandethel.com, where you can find extensive excerpts, audio, and video.

My father was born on November 5, 1922, shortly before Election Day, and died on July 6, 2004, shortly after Independence Day. Although he did not live to see Dear Mom, Dad & Ethel published, he continued to help me revise it, even while on his deathbed.

My father was born on November 5, 1922, shortly before Election Day, and died on July 6, 2004, shortly after Independence Day. Although he did not live to see Dear Mom, Dad & Ethel published, he continued to help me revise it, even while on his deathbed.

Although his dreams of being a flyer were dashed before he was sent overseas, my father considered his military service a high point of his life. It makes sense. After all, his dates and story indicate that he often found himself on the fringes of history.

[Mark Stuart Ellison is a writer, and he has also worked as an attorney and reporter. His articles have appeared in Physicians Financial News, Dutchess Magazine, and The Poughkeepsie Journal. Together with his father, Eli Ellison, he is co-author of the novel Dear Mom, Dad & Ethel: World War II through the Eyes of a Radio Man].

[Mark Stuart Ellison is a writer, and he has also worked as an attorney and reporter. His articles have appeared in Physicians Financial News, Dutchess Magazine, and The Poughkeepsie Journal. Together with his father, Eli Ellison, he is co-author of the novel Dear Mom, Dad & Ethel: World War II through the Eyes of a Radio Man].